‘We got one of the last planes to fly out of the besieged city of Sarajevo. Everyone was terrified and there was a riot at the airport as people tried to get a place on the plane. No luggage was allowed, just people. The airport was a no man’s land, a frontline between warring troops. I have memories of us driving there three days in a row, being turned back. Of walking past tanks. Of long periods of waiting.

You could feel the tired panic, everyone had been living under shell and sniper fire for a long time now and these planes were a sudden lifeline, but sadly, not for everyone. My mother, my brother and my granny; we were lucky. We’d said goodbye to Grandad. I was sat on my granny’s lap, and a man was sitting on the floor in the gap between ours and the seat in front of us. I remember putting my feet on his shoulders. People were crammed into every little space possible. And off we flew. We were very lucky.

The way I came to the UK was crazy, not as crazy as what people fleeing by sea and on foot via smugglers are experiencing today, though. In a similar way, it was not through choice. It was 1992 and the collapse of the former Yugoslavia was already under way, war had already been waged in Slovenia and Croatia (places people associate with music festivals and beautiful scenery today). But still, my family didn’t ever expect that it would get so bad they’d have to leave behind their entire lives.

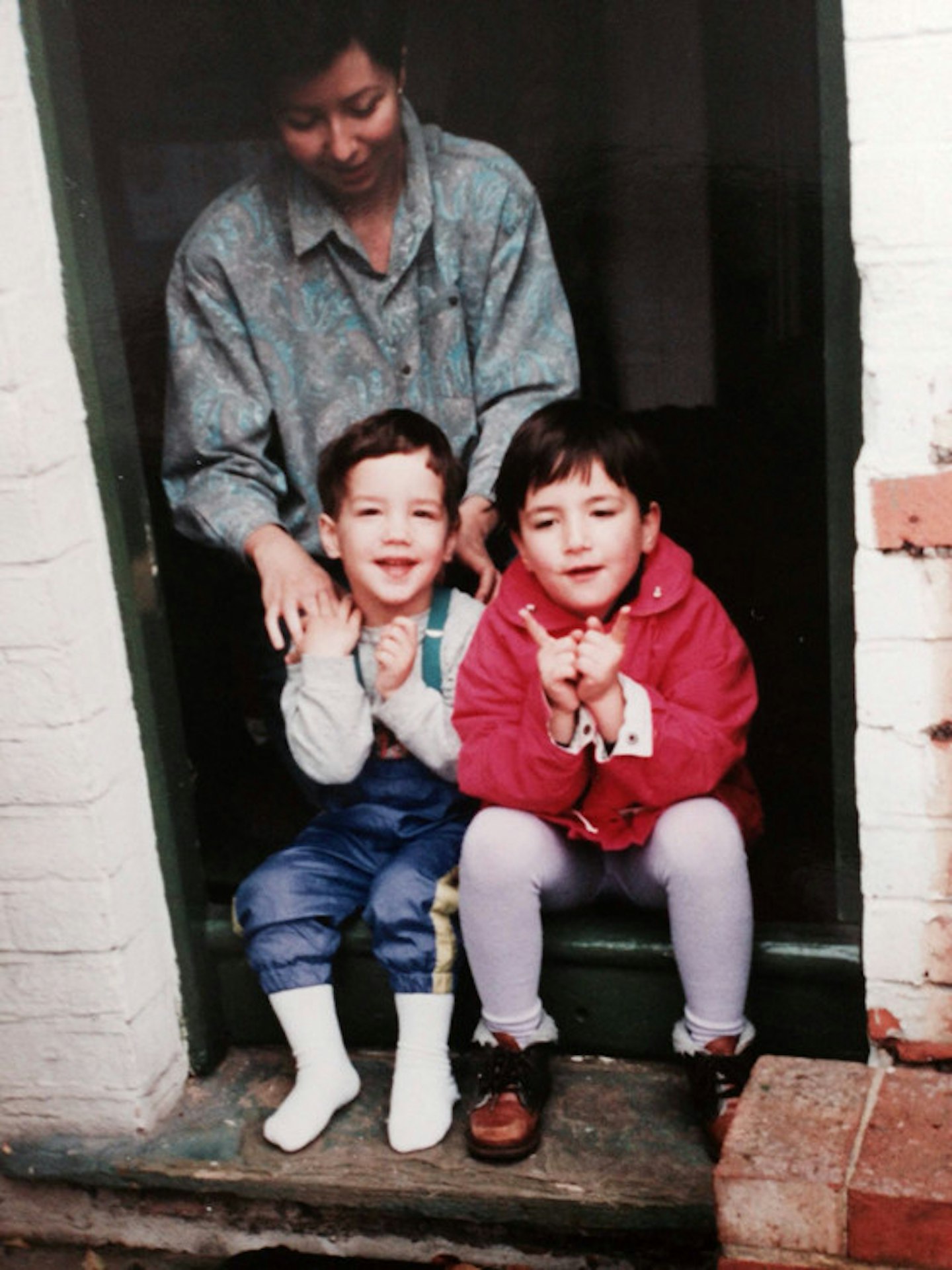

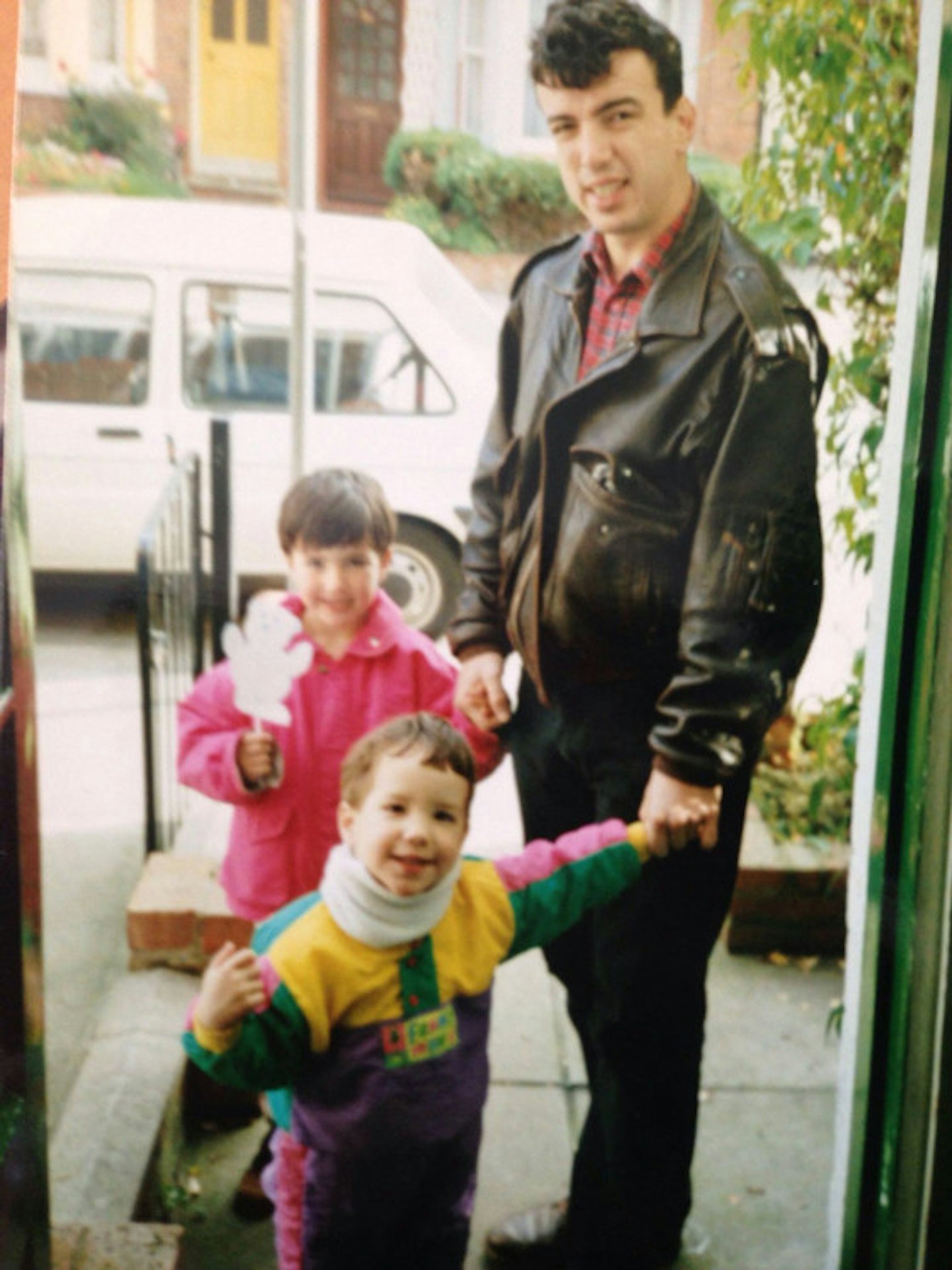

We had an interesting situation – my dad had already been doing a bit of work in London. He was a very well regarded journalist and radio/ TV presenter. The conflict that took ahold of our home came on so suddenly that we were separated from my dad, but once we escaped, this enabled our passage into the UK. No-one ever thought it would be permanent, but in the end, the siege of Sarajevo lasted for almost four years and we ended up staying in England. Eight hundred thousand people fled their homes from Yugoslavia, 8,000 of them were taken in by the United Kingdom.

In the end, the siege of Sarajevo lasted for almost four years and we ended up staying in England

Growing up; that’s the part that’s hard to write about. My granny loves to tell the story of how she found me crying on the stairs of the place we were staying in. She asked me what the matter was. I said I was fed up because every time I touched something in the house I was told to put it down because ‘it wasn’t ours.’

‘Nothing is ours,’ I sobbed. She tried to comfort me with stories of everything we had ‘back home’.

Today, we can go ‘back home’. I go often. But then, she didn’t know, nobody knew anything. It was limbo. It took my dad five years to get his flat back after the war, as people had moved in and refused to leave. He watched them as they took every material object possible, leaving a box of cassettes and my mum’s piano because they didn’t know you could unscrew the legs to get it through the door. But for people coming from countries like Syria and Libya today, however, where entire cities have been razed to the ground, this may never be possible.

My parents said that they never imagined they would end up living in England. They were my age when they had to leave everything behind. They have both said to me that they wished they’d stayed in Sarajevo, but having small children changes your perceptions. I’ve seen people today saying things like ‘Shame on the parents for putting their children on the boats’, but trust me when I say if the streets around you are burning, you’d want to save your babies, too.

My parents said that they never imagined they’d end up living in England. They were my age when they had to leave everything behind

My childhood was a blur of understanding that something wasn’t right and that I was different. Kids at school knew about Bosnia from the television. Of course, some kids were cruel, I was mortified and embarrassed, pretending to be English. But most people were very good to us. Uncle Gerry and Auntie Gladys from the Methodist church down the road became lifelong friends. My best friend, Laura came into my life because our mums met in Oxfam and her mother helped us, asking my mum to teach her piano.

Every Saturday we went to ‘Yugoslav school’ in Ealing Broadway where fellow Yugoslavs came to try and uphold a semblance of memory of home. I didn’t really like it there because it was depressing, all us kids were naughty and angry. But even then I understood that it was an attempt at remembering and holding on to our shattered identity. It’s silly things now that I’m really proud of, which at the time I’d wanted to hide. Different packed lunches. Speaking a different language. These things I celebrate today, but it took a long time.

The biggest lesson I learned was that national identity is a construct. Nations are a man-made construct. Humanity is not. As soon as we overcome the fact that we do not choose where we are born, it ’ a relief, a breath of fresh air. The day I realised this, my life and my struggles with a nostalgic mourning for a home I never had began to fade.

Today, I’m doing very well. I have a wonderful job in film-making, and I like to think that I have given back to the communities that looked after me so well. I can vouch for the fact that having a multi-ethnic community is a gift to our societies. Sharing stories and experiences first-hand do nothing but build us as people. They are what I hold on to the most.

When my granny talks about the past, about how she cried when she accidentally made my birthday cake with salted butter, we can laugh. We can laugh because we were given a chance to rebuild our lives, however wobbly they are today.

National identity is a construct. Nations are a man-made construct. Humanity is not.

Watching events unfold today, it’s hard. The ‘journalist’ kicking refugees as they desperately run through barbed wire put up by Hungary and NATO. Germans greeting refugees as they arrive. Paddy Ashdown tweeting that a ‘minister in the Lords just confirmed refugee orphans and children brought in under Cameron’s scheme will be deported at age 18’.

We have a long way to go, but I do feel like slowly, we’re turning in the right direction.

It took me many years to begin to comprehend what my family went through. The psychological trauma never leaves you. It’s of utmost importance that safe countries such as this one provide support for people who have lost everything – and by everything I go beyond the material possessions that rule out day-to-day lives.

I mean people who have lost their friends, their families, their communities, their homes, their pets, their favourite views, smells, tastes. Identities. Everything that constructs us as human beings is gone. To be given the chance to rebuild is beyond precious. If the people of the UK and Europe began to understand the magnitude of the gift we are so able to give, perhaps decisions of what can be done to help refugees would be more easily made.

And I think we are beginning to understand. In the last week, there has been a change. And it makes me really proud to see people taking matters into their own hands. In August, I went to a protest outside parliament in solidarity with refugees fleeing via the Med. There were 200 people. On Saturday,

. Come along and say hello.

When I was asked to write this, I wasn’t sure what it would be about, exactly. My story is a story shared by so many, but one that’s not told so often, as people like me weave ourselves into new tapestries, and feel lucky and guilty that we made it through. It’s the beginning of an even greater and more extreme story for those just at the beginning. And we can help them.

So I guess this is a call to action, and in the words of my Palestinian friend Lubna Maswra – ‘to be a human being is to act’. We can act in many ways. Talking, as we already are. Learning. Donating to transparent causes. Loving each other. Knowledge and compassion are the greatest power we can possess, in this era of the power struggle.

For generations, especially in this country, we have been taught to be selfish, each to their own. But I think there’s a shift in this and it’s happening now. It’s an exciting time to be part of a movement that’s shifting the powers that rule us. We forget that history is there to learn from and we forget that we are its makers. If there was ever a time to remember this, it is now.’

Like this? Then you might also be interested in:

From Online Petitions To Volunteering – Here’s What You Can Do To Help The Refugee Crisis

Follow Aleksandra on Twitter @AleksandraBilic

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.