I wasn’t eating badly and I was brushing my teeth for two minutes, twice daily. Yet, my gums were bleeding regularly. I’d recently made a pact with myself to stop turning to the internet to self-diagnose (it was January; every sniffle or cough could escalate to something pretty serious after a few minutes on Google), so I pushed this strange thing to the back of my mind. I bought floss.

Not even a couple of weeks later, when I was waking up to go to the toilet more than once throughout the night, and falling asleep at my desk throughout the day, did I think I might be pregnant. But, after feeling totally wasted after one pint at the pub one Friday night, I decided that it wouldn’t do any harm to do a pregnancy test. Something wasn’t right, and I always made an effort to be extra careful about this stuff.

A week later, I found myself in a sexual health clinic in south London, having just been handed a Family Planning Association (FPA) leaflet with the title: ‘Abortion: Your questions answered.’

According to the NHS website, you can refer yourself for an abortion by directly contacting the UK’s two main abortion providers, BPAS and Marie Stopes or through a referral from an NHS professional at a contraception or GUM clinic. I went with the second option, as I thought it’d be good to talk through my options with someone.

When I found out I was pregnant, I was a bit gutted, but I knew from the start that I didn’t want to continue with the pregnancy. However, I had a lot of questions, and I wanted to make sure I got informed answers on how this was all going to pan out.

Women who don’t want to go through with a pregnancy can have a medical abortion, which involves taking two pills (mifepristone and then misoprostol) 24 to 48 hours apart to induce a miscarriage, or they can have a surgical abortion. I began to read the leaflet further. The FPA say it should take five working days from your referral (in person or on the phone) to get a consultation at an abortion clinic, and another five from your decision date to have the abortion. I’d already made up my mind, but the ‘official’ decision has to happen at the consultation (although some women need more time to think and decide after their consultation). The NHS website also says: ‘waiting times can vary, but you shouldn't have to wait more than two weeks from your initial appointment to having an abortion.’ Again, there it was, 10 working days.

This calmed my nerves: In a couple of weeks, this would all be over. I later found out that on this day I would have been around six weeks pregnant. I didn’t expect my abortion to take place bang on 10 working days later, perhaps it would happen a day or two after that recommended waiting time but nothing could have prepared me for how long I had to wait. I waited 40 days from then – around six weeks – from my first referral appointment to the date of the procedure. I was 13 weeks pregnant when I had a surgical abortion, which, if waiting times had been shorter, could have (in theory) happened via medical abortion a lot earlier on. So, why did I have to wait so long?

At my first appointment, when I was sat waiting in the sexual health clinic reading through the FPA leaflet, I was told that I’d have to self-refer to BPAS, as the doctor couldn’t get through – ‘the phone lines are too busy,’ she said. I did so as soon as I left.

To get to the next stage of the process, I had to know my NHS number, weight, and height (so they could note my BMI). All things I probably could have had done at my clinic appointment, but anyway. It was another few days before I could call back with my weight (seriously, who has scales in a rented house), and I then had to book a second telephone consultation for a few days later, where a nurse spoke to me about contraception options post-abortion. During this call, I also booked my consultation at the BPAS clinic, which took place 12 days later (the earliest appointment available). At my consultation, the earliest date offered to me for my abortion was 23 days after that date.

‘Crisis Point’: The Best And Worst Abortion Waiting Times In The Country

While the NHS website and FPA guidelines suggest you shouldn’t be waiting more than two weeks in total for an abortion, it also says that waiting times can vary depending on where you live. So, during a four month-investigation, The Debrief sent Freedom of Information (FoI) requests to NHS Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) across England (the bodies which manage local NHS services) to find out the average waiting times for accessing surgical and medical abortions. If I had to wait - without requesting extra time to consider my decision - surely lots of other people were having to wait too?

Here’s what The Debrief found out:

Increasing waiting times are just one of the obstacles for women trying to access early abortion, a situation which is now ‘at crisis point’, according to one of the UK’s leading experts on women’s healthcare. Professor Lesley Regan, President of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recently told The Guardian: ‘There are a lot of women now who are finding that there are big barriers to them accessing [a] swift response to their request [for an early abortion]. Many women and girls are finding it difficult to access.’

The longest waiting time for a surgical abortion in 2016 was in Leicester, with an average wait of 22.7 calendar days. This is an improvement to its 2012 waiting time (29.1 days), but the figures have been consistently high - more than 20 days - for both medical and surgical abortion since 2012.

The shortest waiting times in 2016 were in Essex (Basildon, Brentwood and the North East area of the region all recorded an average waiting time of fewer than 10 days). Scarborough and Ryedale (9.3 days) and South Devon and Torbay (7.3 days) also fell under the 10-day guideline. The data suggests that you can access early abortion in these places quickly, and their waiting times have stayed at a pretty constant rate since 2012 when I first requested data from them.

Here’s a rundown of the longest average waiting times from 2012-16 (in calendar days) across England, which all exceed the 10-day working day (14-day calendar day) guideline:

The results of The Debrief’s FOI requests showed that between 2015-16, the highest increase in waiting times for a surgical abortion was in Telford and Wrekin in the West Midlands, where women had to wait 12.4 days longer to access a termination than the year previous. Hull has also seen a stark jump in waiting times in the year from 2015-16, despite the number of abortions going down. The number of days taken to access abortion in Hull in 2016 was 11.7 days (not making the top 10), but this was 6.7 days longer than it had previously been (four days).

The next highest increase in waiting times from 2015-16 was in Doncaster, where women had to wait almost a week longer to access abortion in 2016 than the year previous – an extra 6.8 days. Wokingham has seen waiting times increase by 6.3 days in the same amount of time, and women in Lambeth, south London, had to wait an extra 5.9 days in 2016 than they did in 2015.

In the case of Lambeth, where I had my abortion, the numbers definitely don’t match up to my own experience. Lambeth CCG said its average wait in 2016 was 15.7 days, but mine – from my first contact with BPAS to my termination – was 40 days in 2017.

One in three women will get an abortion at some point in their lives, and in England, Wales and Scotland you can get them legally, and safely, up to 24 weeks into your pregnancy (except for Guernsey and Jersey, where it must take place on or before 12 weeks). The 1967 Abortion Act does not apply to Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland.

As well as the Abortion Act stating an abortion has to take place before its 24th week, it also says that it must be authorised by two doctors before it is performed by a registered medical practitioner (aka a doctor). This clause of the Act makes the process unnecessarily time-consuming – in a situation where time is really valuable – and experts have recently called for nurses to be able to administer medical abortion pills to reduce waiting times.

It’s too easy to forget that women aren’t booking referral appointments on the first day of their pregnancy, especially if the pregnancy is unplanned, which half of all pregnancies are. If you’re not trying to get pregnant, you might not even realise that you are until your first missed period. I was six weeks pregnant before I realised (constant fatigue wasn’t unusual for me). And, after all, half the number of women who had abortions in 2016 were usingcontraception. If you take a test two weeks after a missed period, decide to proceed with an abortion, but can’t get a termination for another six or seven weeks, you’re walking around with an unwanted pregnancy for three months.

I spoke to Clare Murphy, head of public policy at BPAS. She said: ‘Once a woman is sure of her decision, she needs to be able to access care as soon as possible. No woman wants to be pregnant for any longer than necessary once that decision has been made.’

High waiting times are even drawing women to access illegal abortion pills online. 'Even though abortion is legal, one you’ve got hurdles, women can take things into their own hands', Clare told me. Indeed, as this study published in September’s Contraception Journalshowed that more than 500 woman had tried to obtain abortion pills online over a four-month period alone. One key problem is the current law can require women to attend multiple appointments for early medical abortion, which can be near-impossible for women with work or childcare commitments. Other women may be in abusive and coercive relationships, which mean they would find to hard to access abortion services in confidence, and services may be a long distance from where they live.

Why Are Abortion Waiting Times Rising?

So, why is it taking so long? The most recent NHS figures for abortions in England and Wales show that the number of abortions taking place has been fairly constant in recent years, indeed if anything they’ve fallen slightly since the mid-2000s according to NHS figures. Clare told The Debrief ‘there are problems in the sector at the moment which are largely related to the provision of Marie Stopes' services, which were suspended last year. Bpas does everything it possibly can to see women as fast as possible in what has been a challenging environment, and waiting times are decreasing all the time.’

What Clare is referring to is the fact that Marie Stopes had some of its services temporarily suspended last year due to concern over the quality of care from the Care Quality Commission (CQC), which had a small knock-on effect on service delivery*. On waiting times specifically, one CQC report, conducted in Merseyside found that ‘patients were not always seen within RCOG recommended timeframes’. Another, conducted in London East recorded that ‘there was no formal monitoring of waiting times or the reasons for any delays’.

Matters are complicated ever so slightly by the fact that local abortion services providers differ slightly, depending on where in the country you live: Marie Stopes, Bpas and the NHS. So which bodies are responsible? Of the worst ten revealed by The Debrief’s FOI requests Leicester NHS trust’s services were NHS operated, Sheffield CCG’s were ‘carried out under NHS contracts’, United Lincolnshire CCG’s were ‘NHS-funded’, South East Staffordshire CCG’s were Bpas, East Staffordshire’s were Bpas, Barnsley CCG said they ‘could not distinguish’ between their figures, Derby Teaching Hospitals Trust and Sutton CCG’s were ‘NHS-funded’ and Cannock Chase CCG fell under Bpas.

‘You are never going to see 100% of women treated within a specific timeframe, as waiting times will also be affected by a woman’s choice – some women may take longer to make up their mind about proceeding, and cancel or not show up for appointments – which is absolutely their right,’ Clare added.

Of course, some women are offered appointments that they don’t want to take at first, as they want some time to consider their decision. But if you know your pregnancy is an unwanted one, the whole process is made much more difficult by what is essentially an outdated Act that expects women to take time off work to see two different doctors, unnecessarily drawing out the time it takes to have an abortion. Indeed, the woman must also attend a specified location to take the pill as it is not currently legal for her to do so at home.

The Debrief also asked Laura Russell, the Policy and Public Affairs Officer of the Family Planning Associaton (FPA) why waiting times could be growing? She explained that it’s exactly for this reason that the FPA is ‘in favour of decriminalising abortion’. Laura explained that ‘abortion should not sit within criminal law. It doesn’t reflect women’s needs or allow for a women-centered service because the way abortion is provided today is not the same as it was 50 years ago. A change in the law would allow for abortion to be regulated like any other medical procedure, and allow the creation of a more women-centered service.’ As she sees it ‘stuff like two doctors signing off and women having to go to specific premises for an abortion, i.e. not being able to take the pill at home does put barriers between women and accessing abortion. The law is not allowing for the best abortion care that we could be providing. It is not flexible enough.’

Professor Lesley Regan, is in agreement. She told The Debrief that the RCOG ‘believes that the current need for two doctors’ signatures to certify that a woman is approved to undergo an abortion causes unnecessary delays in women’s access to abortion services’. Indeed, she emphasised that there are ‘no other situations where either competent men or women require permission from two third parties to make a personal healthcare decision’. Professor Regan firmly believes that doctors should be allowed to ‘provide the assessment in the same way as when they treat their patients without the need to consult another doctor’.

As things stand, if a woman did end her pregnancy without the permission of two doctors, she could technically be sentenced to life in prison under the 1861 Offences Against the Person Act. However, the increasing availability of abortion pills online means that this scenario is far more likely than in the past. Professor Regan says ‘no other medical procedure in the UK is so out-of-step with clinical and technological developments.’

Indeed, as the aforementioned study in September’s Contraception Journal30435-3/fulltext%5D){href='http://www.contraceptionjournal.org/article/S0010-7824(17)30435-3/fulltext%5D' target='_blank' rel='noopener noreferrer'} pointed out, increasing waiting times are actually a reason that women who have chosen to order pills online and carry out an abortion home cite as a key reason for doing so.

There is another factor at play here, as mentioned above the way abortion care is commissioned and delivered has changed. Professor Regan says this is ‘having an impact on doctors’ access to training and women’s access to services’. She added there is ‘low prestige and stigma which may be associated with abortion care’ and this is ‘affecting the morale within the profession’. In England and Wales, Professor Regan said, ‘two-thirds of abortions are performed in the independent sector, meaning junior doctors find it difficult to access training, as there are fewer NHS consultants working in abortion care to train and mentor them’. To address these issues, the RCOG has established an Abortion Task Force, which Professor Regan will be leading.

The Impact Of Rising Waiting Times On Women

Tash*, 25, faced a few obstacles that impacted her waiting time, waiting six weeks from the first time she’d got in contact, to the point of procedure.

‘The waiting time was the most harrowing part of my experience. I was in the middle of my final major project for my MA when I found out I was pregnant,’ she told me. ‘My first point of contact was to go to a free clinic where I had another test. From where I was in my cycle, we worked out I was around five weeks pregnant; I was 11 weeks pregnant by the time I had my termination. I was booked in for an ultrasound – I think it was around 10 days after my appointment at the clinic, and I remember being frustrated that that would be the next contact I would have. I started to get morning sickness symptoms and a deadening lethargy, especially frustrating seeing as I had my MA looming over me still. I remember the ultrasound technician telling me 'whatever you decide to do will be with you for the rest of your life'.

‘I was unto the mercy of the appointment system at that point. I think I did a fair bit of crying on the phone in order to get my next appointment, which was with a doctor to say I really wanted to go ahead with the termination. Then, because I am rhesus negative, I needed to have blood tests taken at another appointment. I had to have an injection after my termination so that my body didn't reject my next foetus, should I decide to keep it. By the time I had done that and an appointment space was free, I was 11 weeks pregnant. I remember spending long weeks drifting in and out of sleep, eating a lot, toying with the decision of keeping the baby, crying and being sick.’

As I’ve said, I was 13 weeks pregnant before I could book in for an abortion. It is safe to say that during this long process I was beginning to feel quite pregnant. In the first trimester of pregnancy (the first 12 weeks), pregnancy symptoms include: morning sickness (which can happen throughout the day and night), severe fatigue, bleeding gums, food cravings, tender breasts, headaches, heightened sense of smell (this could often be the worst), frequent urination and acne. This was the hardest thing about having to wait – the constant, physical reminder that you were playing a waiting game you don’t want to play.

An abortion is safer the earlier you can have it. The sooner it can be dealt with also decreases the impact it can have on your mental health, no woman should be forced to walk around carrying an unwanted or problematic pregnancy for any longer than necessary because of external factors.

I got in touch with BPAS to request counseling, as I began to really struggle with my mental health to a point where I needed to talk to someone about it. It felt like a dark cloud that followed me everywhere. It wasn’t guilt about going through with it – I don't and have never regretted my decision – it was guilt about not being totally OK with it. I’m pro-choice! I’m pro-women. I’m pro-abortion! Why couldn’t I handle this better than I was?

I had a contraceptive coil put in after the termination, and the emotional turmoil I was going through made sex so uncomfortable, that I was sure it had been put in the wrong place. Six weeks after the abortion, I booked an appointment with my GP for a check-up. I wanted to talk about my concern that the coil was in the wrong place. As soon as I sat down in the chair, I burst into tears.

My GP suggested I phoned BPAS to book a counselling appointment with them. She also suggested I go to a sexual health clinic to get a second opinion on the position of the coil. I phoned the counselling number to book an appointment as soon as I got home. It was the 8th of June. I was told the next face-to-face appointment available in London would be on the 11th of August. She then suggested I call the Samaritans: ‘They’re not just for people who are thinking about committing suicide,’ she said. I saw that her intentions were good, but it’s not exactly the kind of thing you want to hear when you’ve already reached a point where you’re seeking counselling. (It is worth saying that BPAS do have a 24-hour aftercare support line for physical after effects).

Feeling pretty disheartened, I took a day off work the week after and went to the sexual health clinic to see if they could tell me if my coil was in the right place. If someone could tell me that everything was physically alright, I’d be able to start moving on, I thought. The first doctor I saw was unsure, even doing an ultrasound, but said they were quite busy and asked if I could come back another day when another doctor was in, for a second – or, in my case, third – opinion. The third doctor I saw confirmed everything was OK with the coil, but suggested I get some counselling. Yes please, I said. She explained that my body and hormones had been preparing for pregnancy, and now that it had gone away, it was natural for my body to be craving it again. I was led into another room where I was told I’d see a counsellor. ‘Oh no, I’m just a support worker,’ he said. ‘I’ll take your mobile number, and when we have a free slot to book you in, I’ll give you a call.’ That was on the 20th of June. It’s now October and I haven’t had a phone call.

Now, with the support of my boyfriend, best friends, and, well, time, I am having more good days than bad. I’m quite certain that if I was able to access the abortion earlier, the emotional effects wouldn’t have been so heavy. Carrying around an unwanted or problematic pregnancy for several weeks is really difficult, especially when you are told at the start that you shouldn’t have had to wait longer than 10 days and that’s what you mentally prepare for. There was also the added strain of feeling like I couldn’t talk to anyone about it because, even today, in 2017, we still don’t really talk openly about abortion.

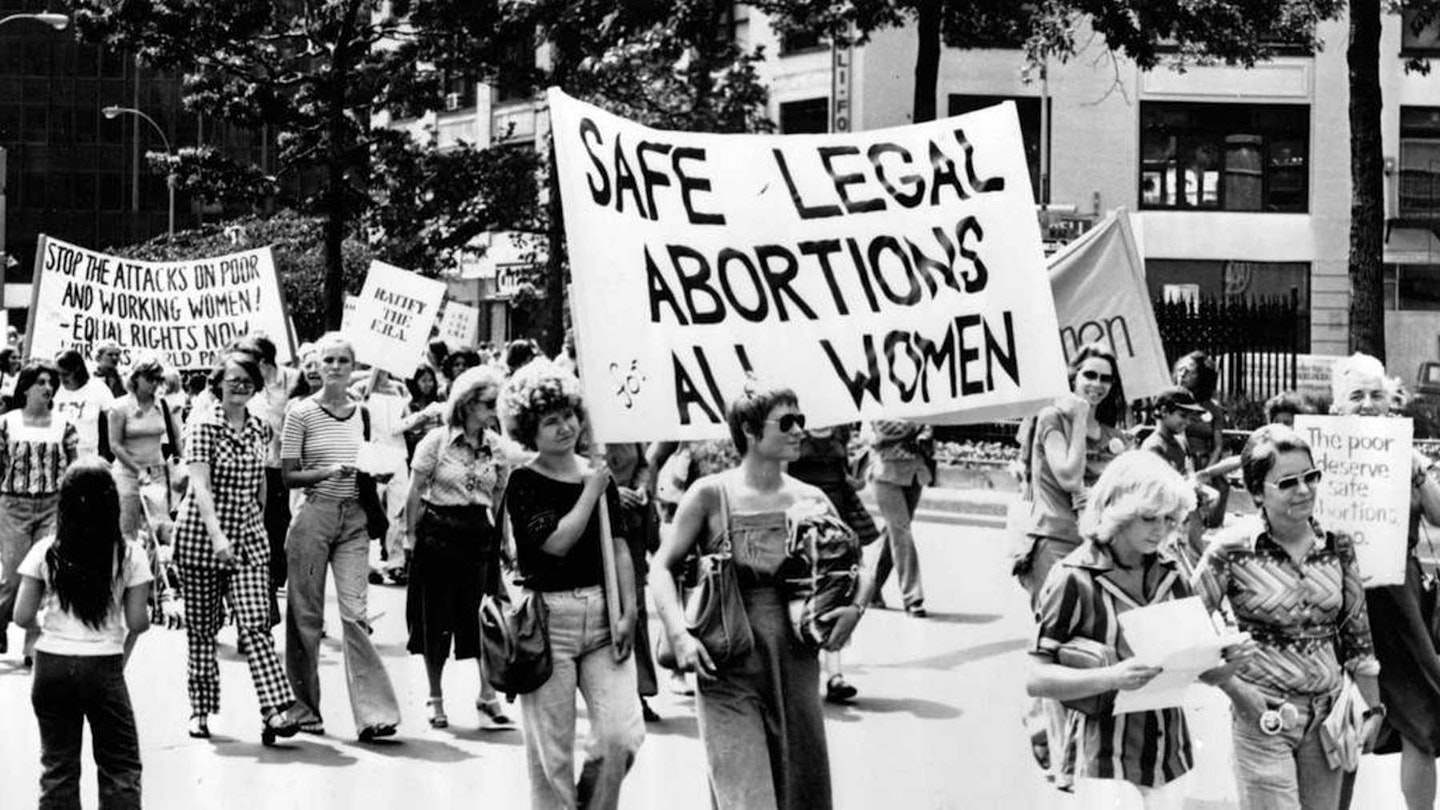

This week marks 50 years of the Abortion Act. We’ve had 50 years of safe and legal abortion in most parts of the UK, with the shameful exception of Northern Ireland. However, with waiting times increasing, early abortion and aftercare support are increasingly hard to access. Its stigma indicates that shame is still being felt by many – and with one in three women getting an abortion at some point in their lives – campaigning for a better quality of care is something all women should be concerned about.

*Names have been changed

The Debrief contacted NHS England for a comment

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.