The tuition fee hike of 2010 was one of, if not the, defining issue of a generation. The collective psyche of an entire age cohort calcified around the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition’s decision to raise fees from £3,000 to £9,000 a year and the large-scale protests which accompanied it.

There’s no doubt that the issue of tuition fees and student loans have been handled badly by successive governments. Most recently, the decision of Cameron’s government to freeze the repayment thresholdhas attracted criticism from Money Saving expert, Martin Lewis, who has pointed out that it is unfair and goes back on what was initially promised. The same government’s decision to axe student maintenance grants, meaning that the poorest students graduate in more debt than those whose parents can afford to bankroll them has also been condemned.

So, it is unsurprising that Labour has set university fees in their sights as part of their manifesto. Instead of raising fees to £9,250 in the autumn as the current government plans to do, Corbyn is proposing that he, if elected, will do away with university tuition fees altogether. It’s a bold and direct appeal to younger voters.

Labour’s last leader, Ed Miliband, didn’t go as far as Corbyn on this issue. In 2015, he proposed cutting fees to £6,000 per year as part of his manifesto. He faced criticism for sitting on the fence as a result of this. Corbyn’s approach is ideologically sound – the principle of free education to those who seek it. It aligns with the founding principle of the NHS: free healthcare at the point of delivery for those who need it. Revealing the policy in Mansfield two weeks ago, John McDonnell, the Shadow Chancellor, saideducation ‘is not a commodity to be bought and sold’. He continued, ‘we want to introduce – just as the Attlee government with Nye Bevan introduced the National Health Service – we want to introduce a National Education Service.’

It’s worth noting that it was actually a Labour government which introduced tuition fees priced at £1,000 a year back under Tony Blair in 1998. That was increased to £3,000 in 2006. The Lib Dems garnered youth support when the promised that, if elected, they would do away with fees. However, once in Government they backed the rise to £9,000.

Doing away with fees ‘once and for all’ sounds good, and there’s no doubt that it would make a lot of students feel a hell of a lot better about going to university. Nobody should feel put off from seeking a university education because of debt but we’ve been here before. So, just how much of a difference will it really make and, where would the money to fund university fees come from instead?

As things stand, the current system is labelled as ‘student loans’ but, in reality, as anyone who makes repayments every month knows, it’s more like paying tax. You only pay when you’re in work, you can’t be chased by bailiffs if you don’t pay, your credit rating isn’t affected and, crucially, what you repay is pegged directly to what you earn. Many have argued that this is actually quite a fair system.

The arguments against tuition fees centred around the idea that the prospect of graduating in tens of thousands of pounds’ worth of debt would deter people from applying to university and increase inequality. However, a 2015 report from UCASfound that '18-year-olds from across the UK were more likely to apply to higher education than in any previous year.’ It also found evidence that ‘In 2015, application rates of 18-year-olds living in disadvantaged areas in all countries of the UK increased to the highest levels recorded.’ Although wealthier families are more likely to send their children to university, the long-term trend of entry rates for students across the socioeconomic spectrum has been upwards in spite of the fee hike.

Indeed, when I interviewed a group of school leavers in Nottinghamshire and asked them what they thought of tuition fees for Radio 4before the last General Election, they all said they thought it was right that they should pay for their university education.

We find ourselves in a situation where student debt has risen to £12.6bn in this country. It was up by 17 per cent to £86.2bn in total last year as the first cohort of graduates to pay the £9,000 fees left university and entered the working world. Experts currently estimate that two-thirds of UK students will never pay off their debt.

Debt, borne by the state, that you’ll never pay back and can’t be forced to repay in exchange for an education? It certainly sounds like a bad policy, but is it students who really suffer? What’s more problematic is the axing of maintenance grants and bursaries that we saw under Cameron, which means that the less money you and your family have, the more debt you’ll graduate in if you choose to go to university. This is certainly harder to justify than the current fee and loan system. Labour have pledged to reintroduce grants for poorer students if elected.

Young people are less likely to vote than any other demographic. Could Labour’s principled proposal convince them to turn up? After all, isn't voting, above all, about our principles?

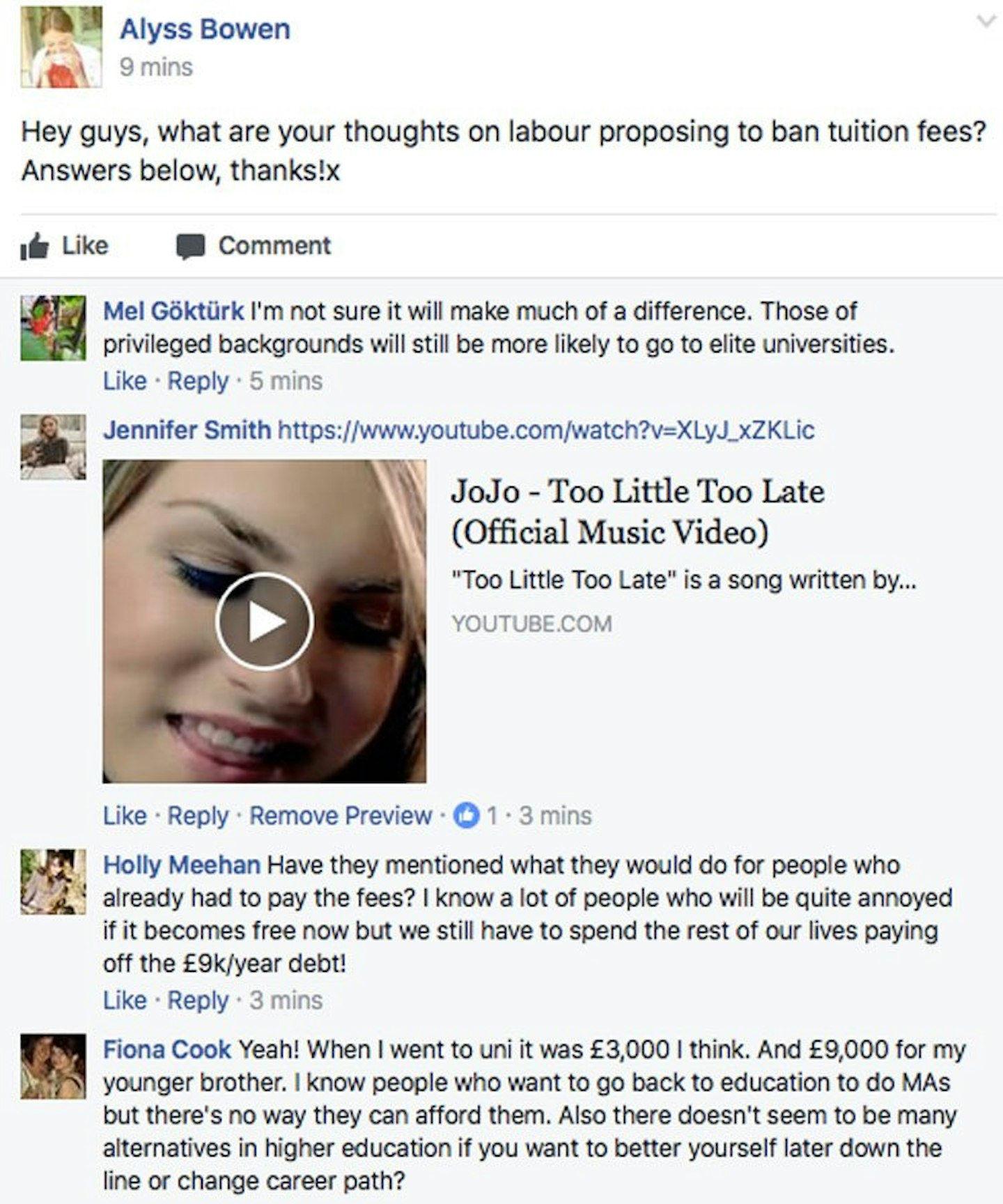

Here’s what Debrief readers think about it:

You might also be interested in:

Bursting The Bubble: How Much Do The Women Of Shipley Care That Philip Davies Is Their MP

Follow Vicky on Twitter @Victoria_Spratt

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.